Latest Posts

- An Introduction to Formal Methods

- Compiling Volatile Correctly in Java

- Formalizing Java's Access Modes

- NP-complete: how hard is that climb?

More posts can be found in the archive.

An Introduction to Formal Methods

This is a somewhat narrow introduction to formal methods I presented at UCLA in March of 2022 with the goal of describing some of my research at Sandia.

Compiling Volatile Correctly in Java

- Shuyang Liu

- John Bender

- Jens Palsberg

The compilation scheme for Volatile accesses in the OpenJDK 9 HotSpot Java Virtual Machine has a major problem that persists despite a recent bug report and a long discussion. One of the suggested fixes is to let Java compile Volatile accesses in the same way as C/C++11. However, we show that this approach is invalid for Java. Indeed, we show a set of optimizations that is valid for C/C++11 but invalid for Java, while the compilation scheme is similar. We prove the correctness of the compilation scheme to Power and x86 and a suite of valid optimizations in Java. Our proofs are based on a language model that we validate by proving key properties such as the DRF-SC theorem and by running litmus tests via our implementation of Java in Herd7

- Preprint (accepted ECOOP'22)

- Project: Herd and Coq formalizations

Formalizing Java's Access Modes

This is my presentation from OOPSLA 2019 on our formal model for the Varhandle API in JDK 9. More information on the paper can be found here. The Coq source and our Herd model/tests have been made available as well.

NP-complete: how hard is that climb?

The purpose of this post is to clarify the difference between NP-hard and NP-complete problems for developers who, like me, have found that the abstract nature of the definitions make developing an intuition for it difficult.

Climbing a Mountain #

Imagine that a friend came to you and said that she would like you plan a trip up an obscure mountain, X. Obviously you need to know how difficult the trip is going to be to do a good job. If it's only a quick day hike to the top you probably just need some sandwiches and water, but if it's a multi-week expedition then you'll need a more comprehensive set of supplies.

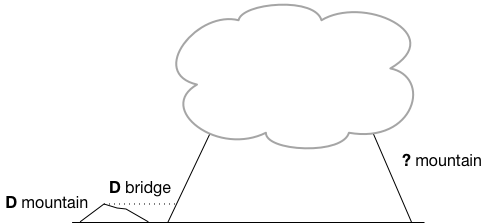

Further, imagine that you are unable to find any information about the difficulty of climbing up mountain X! Your intuitive reaction would probably be to find comparable mountains to get a sense for the difficulty of mountain X using some sort of comparison. Fortunately, right near by there is a mountain Y that is well known. In fact it's close enough that a comparison by height (which we'll use as our proxy for difficulty) is possible save for that fact that peak of mountain X is constantly covered by clouds.

All we really know about mountains X and Y is that X is at least as tall as Y and therefore at least as difficult. We need to get some sense for how difficult mountain Y is so that we can then infer something useful about mountain X. Since we're using vision as our measuring device our system of classification is going to be fairly coarse. That is, if we're positive a mountain can be scaled in a day (think, large hill) then it's probably visually pretty small and if it's going to be on the order of a few weeks then it probably looks pretty serious (think, K2).

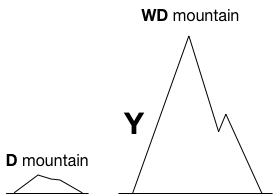

Lets call these two classes of mountains D and WD, for "Day" and "Weeks and Days". When a mountain will take at least a day to hike we say it's D-hard. When it will take at least weeks and days to hike then we say it's WD-hard. So if mountain Y is D-hard then clearly mountain X is at least D-hard and similarly so if Y is WD-hard.

Lets assume that Y is "Weeks and Days"-hard, and that means we know that X is too because it's at least as big as Y. But there's still a problem, we don't know exactly how big mountain X is since the top is obscured by clouds. We only know that it's as as least as hard as Y to climb. If X ends up being as tall as Olympus Mons we should probably just forget it. So, on a clear day when the top of mountain X is visible and comparable to the top of mountain Y you take a look and verify that mountain X is roughly the same size as mountain Y. Now we say that mountain X is WD-complete. That is, we know it's at least as hard as another "Weeks and Days" mountain and we feel confident that it will only take weeks and days and not, for instance, months and years.

This is really great for a couple of reasons. First, we have enough information to start planning a trip to the top of mountain X. Second, because we've classified mountain X as being both WD-hard and "in" the class of WD mountains it stands as an exemplar of that class of mountain, which means we can use it to classify other mountains, in the same way we did with mountain Y.

P, NP, NP-hard, NP-complete #

While you may not be a climbing fan, this serves to illustrate the basic process of establishing when a decision problem is NP-complete by "comparison". To make the analogy clear we'll define, P, NP, NP-hard and NP-complete and link them to the analogy. First though we need to establish exactly what a decision problem is and how Turing machines fit in so that the definitions will make more sense.

NP-hard problems like The Traveling Salesman ( TSP ) are often characterized in their optimization form. In this case the problem is to find the shortest possible route that visits all cities. The decision version is subtly different. The question is changed to whether there exists a path, less than or equal to some length, that visits all the cities. More formally:

Given a graph of cities

Gand a length of tripl, is the pair<G, l>in TSP? Where TSP is the set of all graphs and lengths for which the graph has a trip of length less than or equal to its pairedl.

If an algorithm can tell you whether an arbitrary pair <G, l> is in TSP we say that the algorithm "decides" TSP.

The distinction between these two characterizations may seem like a minor detail especially given that solving the optimization version gives you an answer to the decision version. Later we'll see the fact that the decision version has a yes or no answer is important when we talk about a problem being "in NP" in the same way that mountain X was discovered to be "in WD".

The final bit of required preamble is the Turing machine. I am going to assume some familiarity with Turing machines for the sake of space but when we talk about algorithms and their complexity we're talking about those algorithms and a corresponding Turing machine. The choice of the Turing machine as the model for discussions in complexity is due to it's incredibly robust and universal nature [1] though we won't explore that here. In particular we can feel confident that when we say a Turing machine operates in polynomial time it isn't due to some cleverness that we employed in the construction of the Turing machine [2].

Polynomial Time #

Informally the class P is the class of problems that can be solved in polynomial time, or in other words the class of problems that can be solved in a number of steps that is a polynomial function of the size of the input. A slightly more formal definition of polynomial time problems:

A problem is in P if there exists a Turing machine that can decide an instance of the problem in a number of steps that is a polynomial function of the size of the input.

Again, deciding a problem means determining an instance's inclusion in the set for the problem (eg, whether a graph and length <G, l> are in TSP).

In terms of our analogy, P corresponds with the day hike category, D. That is, efficiently solvable problems equate with easily hikeable mountains. I think it's initially hard to swallow polynomial functions like n5 as "efficient" since they can clearly grow quite quickly with the size of the input. The key is that polynomial time functions represent some sort of cleverness in finding a solution. With a polynomial time function it's certainly not the case that all the possibilities for a given input have to be tried to determine the answer.

Non-deterministic Polynomial Time #

Contrary to the section title we're going to use the more popular definition of NP, which is that of a verifying Turing machine that can take an instance of a problem and some "certificate" that convinces the Turing machine to decide positively for the instance. This definition and that of the non-deterministic polynomial time Turing machine are equivalent [3] but the first requires a less detailed discussion of Turing machine so we adopt it here.

A problem is in NP if there exists a Turing machine that can decide an instance of the problem in polynomial time given a certificate of size polynomial in the size of the instance.

Instead of solving the problem directly, problems in NP require a Turing machine that can check the problem given some extra information. In most (all?) cases the certificate is the solution to the problem. For the traveling salesmen, the certificate would be a path that covers all cities in G that has a total length less than or equal to l.

Note that the certificate must be polynomial in the size of the problem instance or the Turing machine wouldn't be able to read the certificate in polynomial time let alone use it for verification! Again, for TSP the certificate is a subset of the edges of the graph (a path with length <= l) so it's linear in the size of the input.

In our analogy, NP problems equate with weeks and days long hikes, WD. While WD is fairly abstract in terms of difficulty NP problems are very precise in that they require that a solution can be verified in polynomial time given some certificate. Also, just like the mountains, all problems in P are in NP in the same way that all day long hikes can also be done in weeks and days if you like to take your time. The containment of P in NP follows from observing that each polynomial time Turing machine can act as a polynomial time verifier for a problem instance by simply ignoring the certificate and generating the solution directly.

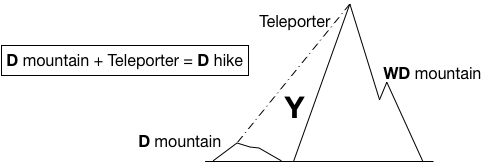

A slight departure from our analogy is that the distinction between D and WD is fairly clear. It's possible that in some distant future there will be shortcuts to the top of mountains like K2 and Everest that will make them surmountable in a day (teleportation?), but intuitively day hikes and weeks long hikes are very different things. Not necessarily so for P and NP. For good reason [4] it is strongly believed that P is not the same as NP though it has yet to be shown conclusively. Further, the definitions ask nothing that might automatically differentiate the two classes and so whenever we distinguish between P and NP it comes with the caveat that it is still possible they are the same class of problem however unlikely that may be.

Polynomial Time Reduction #

We used vision to compare mountains but for the complexity of decision problems we need something more precise. The primary tool for comparison in complexity is the reduction. A reduction is a sort of translation and it's valid if the translated problem's solution implies a solution to the original problem and vice versa.

A problem is polynomial time reducible to another problem if there exists a Turing machine that can translate any instance of the first problem to the second such that the original instance has a solution if and only if the reduced instance has a solution and if the reduction operates in polynomial time.

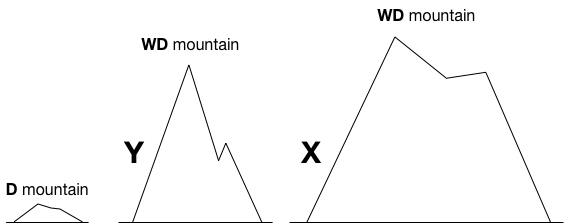

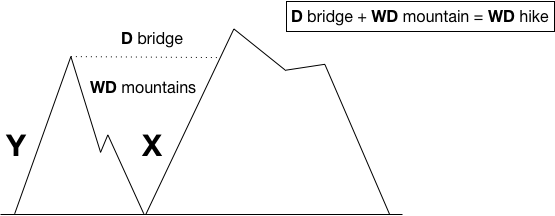

Understanding this is absolutely essential to understanding what it means for a problem to be NP-hard, so we're going to abuse the mountain climbing analogy just a bit to help. Instead of measuring the relative difficulty of a climb by sight, we'll introduce a more serious restriction on how to compare mountains. To match the reduction problems we'll require that a bridge be built between mountains.

Leaving aside the normal lateral distance it's definitely the case that the bridge should only take days to hike, otherwise in the process of crossing the bridge you might end up climbing a different class of mountain! This corresponds to the requirement that our reduction between problems should take polynomial time.

This is important because if you could devise some special bridge (teleporter?) that allowed you to cross from the top of a weeks and days mountain to the top of a day trip mountain in the length of a day trip, you'd have a way to scale that weeks and days mountain in about a day by climbing the day trip mountain and then taking the bridge.

In essence you will have shrunk the bigger mountain! Further, if you have "day trip bridges" between that first big mountain and other big mountains then you could get to the top of any them with a relatively short trip. The hiking world would be changed forever [5].

NP-hard #

It's this type of reduction that defines what it means for a problem to be NP-hard. We say that a problem is NP-hard if it can be compared to any other problem in NP by means of a reduction in the same way that we can classify mountain X by means of a "reduction" or "bridge" from mountain Y. The seeming impossibility of building a day trip bridge from a weeks and days mountain to a day trip mountain ensures that if you can build that bridge one of two things has happened:

- You've come up with an absolutely ground breaking bridge building technique.

- The target mountain is also at least a weeks and days mountain.

In the same way, if you can come up with a polynomial time reduction to some problem from a problem that is NP-hard but also in NP then you've either come up with a ground breaking reduction or your problem is also NP-hard.

It's also important to note that if we want to get an understanding for how difficult mountains are the bridges must be from tops to tops. That is, you could build a day bridge from the top of a day mountain to the side of a much bigger mountain but that wouldn't tell you a whole lot about the much bigger mountain.

Similarly you can reduce from polynomial time problems to NP-hard problems but it's not going to mean a whole lot, which is why we reduce from problems known to be NP-hard and in NP [6].

NP-complete #

Recall that when a mountain is WD-hard like X was before the clouds cleared we said that it was going to take at least weeks and days to climb; it could take more. Again NP-hard gives the same characterization for problems. When we say that something is NP-hard we're simply saying that it's at least as hard as any other problem in NP but it could be harder.

So in addition to knowing whether a problem is NP-hard, if we can also show that a problem is in the class NP, we say that it is NP-complete and that it represents a prime example of the class. This is precisely why the optimization form of TSP can only be said to be NP-hard and not NP-complete because verifying the optimal solution for a given graph of cities will take as long as generating the solution in the first place, so there's no way to build an algorithm that can verify that a given solution is optimal in polynomial time. On the other hand if we tweak the question and ask whether a graph has a solution of a certain length then we can certainly check that in polynomial time placing it firmly in NP!

If the mountain is both WD-hard and also in the WD class it's a WD-complete mountain. If a problem is NP-hard also in NP it's an NP-complete problem.

Closing #

If we want to know just how hard a problem is in terms of computation it's really not enough to know that it's at least as hard as another problem for the same reason we must know more about a mountain before we can plan to climb it. Ultimately we want to define our problems as complete for some complexity class so that we can clearly say to our hiking friends just how hard the climb will be.

Footnotes #

- Wikipedia - Church-Turing Thesis

- "logarithmic slowdown in simulation". - Wikipedia - Turing Machine

- Wikipedia - NP Machine Definition

- "n particular, if P = NP, then the hierarchy collapses completely." - Wikipeda - Polynomial Hierarchy

- I'm not bothering to mention that the requirement is that all problems in NP have a reduction to the problem under consideration because I don't want to bother with Cook/Levin, Wikipedia - Cook Levin Theorem.

- This is a sort of sidelong glance at the directionality of reductions being from the existing NP problem to the unknown.